Submitted by Anju George

Planning for Multiculturalism: The Case for Equity and Justice in Communities

Canada Architecture News - Apr 25, 2023 - 09:00 906 views

Multicultural planning has slowly but steadily been growing in importance. There have been arguments that speak to the failure of multicultural planning advocacy translating into effective multicultural planning practice. Multicultural planning has been discussed with respect to marginalized and/or disenfranchised groups predominantly, but not so much on pluralistic planning pertaining to multi-ethnic groups. As minority groups have often been pushed to the sidelines, inclusive physical and/or spatial planning may actually be the answer to effecting change. But the research on inclusive physical planning within multicultural planning literature is limited at best. The concepts of equity and justice have not been analyzed as much either within the realm of multicultural planning. This article (and my future research) will help to have those discourses within multicultural planning, and can aid in formulating a policy framework for multicultural spaces in Canadian communities than can incorporate the tenets of equity and justice.

In 1971, Canada was the very first country in the world to float a Multiculturalism Policy under the Liberal Party of Pierre Trudeau. The concepts of equity and justice have been contextualized within this and other Multiculturalism Acts, but have not really penetrated into multicultural planning policy and practice.

Evolution of equity and justice within the realm of multicultural planning

Multicultural planning is essentially planning for multiculturalism that calls for an awareness of race and culture among planners and elected officials1. The amalgamation of the concepts articulated by Sandercock, Qadeer, and Fincher on diversity/multicultural planning brings about an adaptive, recognitional form of planning that engenders inclusive multiculturalism which speaks to the involvement of different ethnic, cultural, minority and/or disenfranchised communities (in terms of power and income inequalities) in planning processes and policies2,3,4,5.

Recognitional Planning: Planning for the disenfranchised

Krumholz believed in the ideology of equity planning, which fundamentally meant planning for those who belonged to the weaker and poorer sections of society; this meant that planners would need to be especially conscious of the political and professional facets of planning problems in order to become thoroughly conscientious6. Though equity planning is critiqued for its utopianism regarding how planners’ actions play out in the real world because of their inability to influence the implementation of plans, planners need to be able to overcome the barriers of political unwillingness in order to catalyze policy change for the disenfranchised7.

Harvey and Fainstein advance the idea of addressing the needs of the marginal and powerless, and include those whose diverse needs are categorized based on race, ethnicity, immigration status, age and gender. With the plurality of competing interest groups, the universality and homogenization of an overarching public interest that masks heterogeneity and rests on the supremacy of scientific reasoning becomes all the more problematic8,9,10.

Multicultural Planning: Renewed version/Expansion of recognitional planning

The term multicultural is ambiguous with regard to its meaning and scope. Planners can find the answer in addressing ethnocultural diversity with adaptive and responsive planning, rather than being preoccupied with the term’s ambiguity11. Diversity is also a term that has several meanings within urban literature12.

As contemporary social movements began mobilizing for justice around issues concerning ethnicity, nationality, race, gender, and sexuality, in Western industrialized countries in the 1960s and 1970s, the term ‘multiculturalism’ started gaining prominence in planning and policy discourse. Pluralist planning gradually replaced monistic planning that ignored the needs of disenfranchised groups, and broadened its scope from a singular concern for the physical environment to advocacy planning for the disadvantaged groups13. As a result, cosmopolitanism, which meant being open to and having an appreciation for cultural diversity, started gaining traction14. Intercultural dialogue that provides a platform for authentic dialogue, which engages marginalized people, individually and as a collective force, should normatively take into account critical multiculturalism as a social movement that provides opportunities for minority groups to live together in a diverse society symbolized by mutual respect and understanding15.

Healey proposes communicative planning to be conducive to the challenges presented within multicultural contexts16. She advances the idea of intercultural dialogue that is reflective of the diverse meanings and understandings that proffer respect for individual and cultural differences. Campbell and Marshall acknowledge the fragmented, fluid dynamics of multicultural societies of the western world, and ask whether communities of shared interests can even be identified in such complex scenarios17.

Hoernig and Walton-Roberts emphasize that a lot of the conceptualizations of the city have fallen behind with respect to the explicit recognition of cultural diversity and ethnic difference, and propose for a transformative multiculturalism that “draws upon cultural difference to destabilize the status quo and work toward more equitable, intercultural relations”18. The theory of hyper-diversity has been introduced to shed light on cultural pluralism that goes beyond mere ethnicity to explore differences between attitudes, activities and lifestyles among diverse (immigrant) populations19.

In the world of literature that surrounds the contextualization of cultural diversity within the realm of urban planning, the theoretical dilemmas concerning difference are not really reflected in planning practice20. The concepts of equity and justice have been discussed in a lot of the planning literature on participatory planning theory, but have not been discussed as much in the literature on multicultural planning. A lot of the planning scholars speak to the idea of pluralism and multiculturalism in a way that addresses marginalized and/or disenfranchised communities alone, and not in a way that addresses different identities and/or multi-ethnicities (in the way that I have framed what multicultural planning encompasses).

Influence of multicultural planning on physical and spatial planning

Though spaces are physical, the effects these spaces have on users can both be physical and intangible. As planners, who are not urban designers, the onus is on us to be able to tease out the intangible as well, and not think of spaces as physical entities alone. Since places are integral to human existence, the attributes and qualities that distinguish places from one another need to be carefully thought out as well21,22,23. Places are relational constructions, and can have different meanings when experienced by different social, cultural and/or ethnic groups24.

'Grit' laneway murals reflect diversity of Toronto's neighbourhoods. Image via TO Times

There are some planners who acknowledge the fact that multiculturalism is transforming the environments (both urban and suburban) in which they function along with the assumptions (cultural and other) they once upheld. Despite the reluctance of some planners to accommodate for diverse ethnicities and cultures, and their insistence on basing their planning decisions on the technical/scientific qualities of the proposal, the dilemmas and complexities attributed to multiculturalism cannot be ignored from planning practice and policy25. As multicultural planners and designers, we ought to create meanings out of those places by invoking a sense of place. A multicultural approach to planning would need to acknowledge that the experiences and priorities of different cultural communities be taken into account when making decisions about the design and development of their spaces. Sandercock advocates for invoking a sensibility that caters to the emotional and political economies of cities; that is alert to the diverse publics of the city and the city senses of sound, smell, taste, touch and sight; and that is responsive to the desires of all its citizens and the physical infrastructure26.

Public Realm

Just as public spaces are heterogeneous and ambiguous, the concept of integration is also complex through discourses and/or practices followed within the realm of multiculturalism27. Like the aforementioned sentence suggests, these spaces can range from a community centre in a neighbourhood that holds programs for welcoming immigrant communities or a park where people gather around after work to a congregational place of worship that provides support (social and/or cultural) to diverse communities. Like de Certeau observed in Basu & Fielder’s article, these then become ‘polyvalent’ spaces that can take on many forms where the experience of integration is both fragmented and incremental; fragmented because of the different ways in which migrants navigate these very spaces, and incremental because of how they form networks of affiliations with the multiplicity of these places28. Mixed-life public spaces are inherently diverse, democratic and inclusive29.

These spaces can also be underutilized and vacant spaces that are not essentially planned spaces, where ‘empowering’ relationships can be formed through community building30. The terms of engagement or micropolitics of the public sphere (through everyday social contact and encounter) are crucial for overcoming and reconciling ethnic differences, as these are platforms for open dialogue that may not necessarily end in consensus31.

The dearth of information pertaining to the influence of multicultural planning on physical and spatial planning is evidenced by the findings from the conducted literature review discussed in the aforementioned written section. Most of the papers discuss planning for communities that are primarily identified by their marginalized/disenfranchised statuses alone and not by their cultural/ethnic identities.

Implications of multicultural planning interventions for equity and justice

As Galanakis observes, Toronto is a multicultural, multiethnic, multilingual city of striking contrasts, it also happens to be a city of socio-spatial polarization32. Multicultural planning interventions can have a number of implications for equity and justice. All the same, these interventions may also have the potential to create new forms of inequality and injustice through the reinforcement of power imbalances and the exclusion of certain groups. Discerning the actions committed by planners (sometimes complicit) in perpetuating racism is the need of the hour as there is no doubt that racial discrimination is systemic, and is tied to public policy even now33.

A Black Lives Matter protest held in Montreal in June, 2020. Image © Michael Passet, Shutterstock.com

Fincher introduces the idea of recognizing and supporting accessible spaces that encourage convivial interaction to be included in planning thought38. With respect to social planning aims, apart from planners only thinking about developing community that is realized as an attempt to help people foster long-term relationships and connections to a specific place, they can also be tasked with facilitating opportunities for conviviality that encourages autonomous, fleeting, often spontaneous encounters that may result in participants experiencing a special sense of belonging39. Even though a respect for difference may be generated from particular kinds of micro-public encounters, concerns regarding the scaling up of such encounters remain, considering that White majority prejudices are rooted in narratives around economic and cultural victimhood, wherein established certainties are being continuously eroded by unprecedented socioeconomic change40. Valentine proposes an urban politics that addresses inequalities of a real and perceived nature by identifying the need to unite seemingly disparate debates around prejudice and respect with questions regarding inequalities and power relations41.

Although the public realm is principally plural exhibiting the polyphonic nature of the community, it is contested because of the competing discourses that reflect political and historical power maintaining the status quo of a single hegemonic story of the ruling class42. Being heavily reliant on commonality rather than difference can conceal the inherent plurality of communities, where artwork and memorials commemorate European colonial history while the erasure of the histories and identities of Indigenous and other peoples (Black and other people of colour) occurs on a regular basis43.

The Chinatown neighbourhood after dark in Toronto. Image © José Ramírez, Unsplash.com

Ethnic enclaves are a spatial manifestation of cultural diversity on the ground44. All the same, the issues associated with the integration of ethnic enclaves within the diverse cultural urban fabric and the reconciliation of different ethno-cultural interests with the overarching goals of equitable development and fair housing remains to be confronted45. Zhuang discusses the (c)overt racism and discrimination, along with the conflicts that arise between immigrants and established community members, who perceive differences along racial, class and ethnic lines to be threats to the stability of the neighbourhood46.

The article suggests that the benefits of citizen participation do largely outweigh the cons, but only if done earnestly and with extreme caution. Planners are compelled to acknowledge the market forces that continually erode influence the democratic face of good governance. Within an inclusive participatory association, governance systems that are beyond-the-state may prove to be heavily networked and foundationally based on the interactive relationship between actors who share a high level of trust amidst internal conflict and opposing agendas, but their incorporation into (informal) grassroots civil activism can be precarious with respect to representation47.

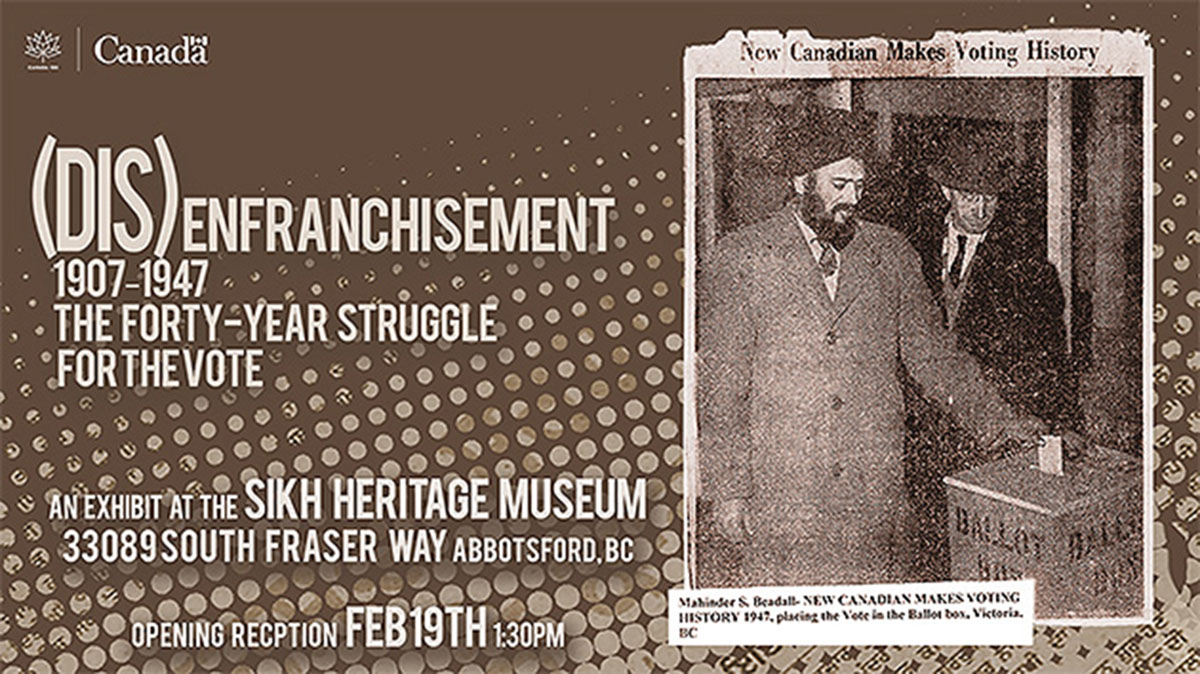

An exhibit organized by the students of University of the Fraser Valley's Centre for Indo-Canadian studies to attain the vote for Indo-Canadians in 2017. Image via UFV Today

Conclusion: Towards devising a framework for multicultural planning

Based on a critical assessment of the relevant literature, multicultural planning requires active engagement with diverse cultural communities and the incorporation of their different perspectives and needs into the planning process, and also mandates addressing the issues of discrimination and inequality that can be propagated by inefficient planning practices. Since the values and norms upheld by the dominant culture are legislated in both the current frameworks of planning and in the practices of planners, they are not in alignment with the principles of multicultural planning, as has been elucidated in this article48.

Equity and justice narratives would need to be able to permeate equitable public policy and inclusive guidelines resulting in the creation of truly pluralistic, multicultural communities. As Sandercock has proposed, restructuring the planning system is absolutely critical - by reformulating legislation, challenging the same through a regulatory framework for its consistency with antidiscrimination and/or endorsed multicultural policies49. Municipal policymakers are yet to be fully informed of the challenges that immigrant communities are confronted with and the roles (direct and indirect) they play in moulding ethnic neighbourhoods50.

An important condition for planning to be genuinely multicultural is for the planning process to be able to evolve and transform by ensuring uniformity pertaining to the access to and the effective delivery of planning services to traditionally marginalized groups discriminated against by the planning process51.

References

1. Qadeer, M. A. (1997). Pluralistic Planning for Multicultural Cities: The Canadian Practice. Journal of the American Planning Association, 63(4), 481-494.

2. Sandercock, L. (2000). Cities of (In)Difference and the Challenge for Planning. DisP - The Planning Review, 36(140), 7-15.

3. Sandercock, L. (2009, January 01). From Nation to Neighbourhood: Integrating Immigrants through Community Development. Plan Canada, Special Edition, 06-09.

4. Qadeer, M. A. (2009). What is this thing called multicultural planning? Plan Canada: Special Edition: Welcoming Communities: Planning for Diverse Populations, 10-13.

5. Fincher, R. (2003). Planning for cities of diversity, difference and encounter. Australian Planner, 40(1), 55-58.

6. Krumholz, N., & Forrester, J. (1990). Making Equity Planning Work: Leadership in the Public Sector. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

7. Krumholz, N., & Hexter, K. W. (Eds.) (2018). Advancing Equity Planning Now. Cornell University Press.

8. Harvey, D. (1992). Social Justice, Postmodernism and the City. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 16(4), 588-601.

9. Fainstein, S. S. (2000). New Directions in Planning Theory. Urban Affairs Review, 35(4), 451-478.

10. Campbell, H. & Marshall, R. (2002). Utilitarianism’s Bad Breath? A Re-evaluation of the Public Interest Justification for Planning. Planning Theory, 1(2), 163-187.

11. Qadeer, M. A. (2015). The Incorporation of Multicultural Ethos in Urban Planning. In M. A. Burayidi (Ed.), Cities and the Politics of Difference: Multiculturalism and Diversity in Urban Planning (pp. 58–86). University of Toronto Press.

12. Fainstein, S. S. (2005). Cities for diversity. Should we want it? Should we plan for it? Urban Affairs Review, 41(1), 3-19.

13. Burayidi, M. A. (Ed.) (2000). Urban Planning in a Multicultural Society. Westport, CT: Praeger.

14. Umemoto, K., & Zamonelli, V. (2012). Cultural Diversity. In R. Crane & R. Weber (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Urban Planning (pp. 197-217). Oxford University Press.

15. Stokke, C., & Lybæk, L. (2018). Combining intercultural dialogue and critical multiculturalism. Ethnicities, 18(1), 70-85.

16. Healey, P. (1999). Institutionalist analysis, communicative planning, and shaping places. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 19(2), 111-121.

17. Campbell, H. & Marshall, R. (1999). Ethical Frameworks and Planning Theory. International Journal of Urban of Urban and Regional Research, 23(3), 464-478.

18. Hoernig, H., & Walton-Roberts, M. (2009). Multicultural City. In R. Kitchin & N. Thrift (Eds.), International Encyclopaedia of Human Geography (pp. 201-210). Elsevier Science.

19. Dean, J., Regier, K., Patel, A., Wilson, K., & Ghassemi, E. (2018). Beyond the Cosmopolis: Sustaining Hyper-Diversity in the Suburbs of Peel Region, Ontario. Urban Planning, 3(4), 38-49.

20. Perrone, C. (2011). What would a “DiverCity” be like? Speculation on Difference-sensitive Planning and Living Practices. In C. Perrone, G. Manella & L. Tripodi (Eds.), Everyday Life in the Segmented City (Vol. 11) (pp. 1-25). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

21. Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

22. Lynch, K. (1984). Good City Form. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

23. Norberg-Schulz, C. (1979). Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. Rizzoli.

24. Norberg-Schulz, C. (1979). Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. Rizzoli.

25. Wallace, M. (2000, July-September). Where Planning Meets Multiculturalism: A View of Planning Practice in the Greater Toronto Area. Plan Canada, 40(4), 19-20.

26. Sandercock, L. (2004). Towards a Planning Imagination for the 21st Century. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70(2), 133-141.

27. Basu, R., & Fiedler, R. S. (2017). Integrative multiplicity through suburban realities: exploring diversity through public spaces in Scarborough. Urban Geography, 38(1), 25-46.

28. Basu, R., & Fiedler, R. S. (2017). Integrative multiplicity through suburban realities: exploring diversity through public spaces in Scarborough. Urban Geography, 38(1), 25-46.

29. Lesan, & Gjerde, M. (2021). The role of business agglomerations in stimulating static and social activities in multicultural streets. Australian Planner, 57(1), 65-84.

30. Amin, A. (2008). Collective culture and urban public space. City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action, 12(1), 5-24.

31. Amin, A. (2002). Ethnicity and the multicultural city: Living with diversity. Environment and Planning A, 34, 959-980.

32. Galanakis, M. (2013). Intercultural Public Spaces in Multicultural Toronto. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 22(1), 67-89.

33. Marcuse, P. (2012). Justice. In R. Crane, & R. Weber (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Urban Planning (pp.141-165). Oxford University Press.

34. Turok, I., Kearns, A., & Goodlad, R. (1999). Social exclusion: in what sense a planning problem? Town Planning Review, 70(3), 363-384.

35. Zhuang, Z. C. (2020). Cities of Migration: The Role of Municipal Planning in Immigrant Settlement and Integration. In International Affairs and Canadian Migration Policy (pp. 205-226). Springer International Publishing.

36. Zhuang, Z. C. (2020). Cities of Migration: The Role of Municipal Planning in Immigrant Settlement and Integration. In International Affairs and Canadian Migration Policy (pp. 205-226). Springer International Publishing.

37. Zhuang, Z. (2021). The Negotiation of Space and Rights: Suburban Planning with Diversity. Urban Planning, 6(2), 113-126.

38. Fincher, R. (2003). Planning for cities of diversity, difference and encounter. Australian Planner, 40(1), 55-58.

39. Fincher, R. (2003). Planning for cities of diversity, difference and encounter. Australian Planner, 40(1), 55-58.

40. Valentine, G. (2008). Living with difference: Reflections on geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 32(3), 323-337.

41. Valentine, G. (2008). Living with difference: Reflections on geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 32(3), 323-337.

42. Toolis, E. E. (2017). Theorizing critical placemaking as a tool for reclaiming public space. American Journal of Community Psychology, 59(1-2), 184-199.

43. Toolis, E. E. (2017). Theorizing critical placemaking as a tool for reclaiming public space. American Journal of Community Psychology, 59(1-2), 184-199.

44. Qadeer, M. A. (2015). The Incorporation of Multicultural Ethos in Urban Planning. In M. A. Burayidi (Ed.), Cities and the Politics of Difference: Multiculturalism and Diversity in Urban Planning (pp. 58–86). University of Toronto Press.

45. Qadeer, M.A., & Agrawal, S. K. (2011). The Practice of Multicultural Planning in American and Canadian Cities. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 20(1), 132-156.

46. Zhuang, Z. C. (2020). Cities of Migration: The Role of Municipal Planning in Immigrant Settlement and Integration. In International Affairs and Canadian Migration Policy (pp. 205-226). Springer International Publishing.

47. Swyngedouw, E. (2005). Governance Innovation and the Citizen: The Janus Face of Governance-beyond-the-State. Urban Studies, 42(11), 1991-2006.

48. Sandercock, L. (2000). Cities of (In)Difference and the Challenge for Planning. DisP - The Planning Review, 36(140), 7-15.

49. Sandercock, L. (2000). Cities of (In)Difference and the Challenge for Planning. DisP - The Planning Review, 36(140), 7-15.

50. Wood, P. K., & Gilbert, L. (2005). Multiculturalism in Canada: Accidental Discourse, Alternative Vision, Urban Practice. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 29(3), 679-691.

51. Burayidi, M. A. (Ed.) (2015). Cities and the Politics of Difference: Multiculturalism and Diversity in Urban Planning. University of Toronto Press.

Top Cover Image: Indian dancers from the state of Punjab dance in front of the Chalo! FreshCo. store in Brampton. Image via Sobeys.